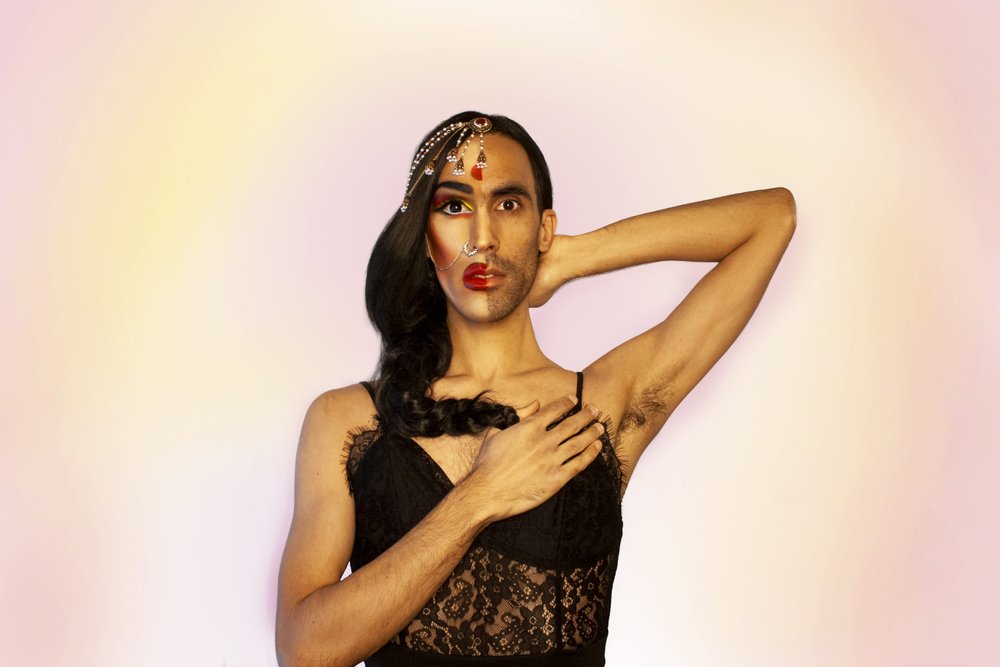

Quebec-born interdisciplinary artist Gabriel Dharmoo unveils a joy-filled full-length drag show

BY ALEXANDER VARTY, STIR VANCOUVER

The Queer Arts Festival presents Bijuriya at the Roundhouse Community Arts and Recreation Centre on June 28 at 7 pm.

UNLESS YOU’RE FLUENT in Hindi, you’re not going to grasp the full import of Bijuriya’s name and ambition on first meeting—even if the Montreal-based drag artist’s moniker can be parsed in both of Canada’s official languages. One could, for instance, read the name as a Desi-fication of the bilingual term “bijou”, which the online Oxford dictionary tells us means “small but attractive and fashionable”.

Bijuriya’s stage presence is anything but small, although her creator, Quebec-born interdisciplinary artist Gabriel Dharmoo, is of medium height and preternaturally slim. She’s certainly fashionable, if one’s taste in couture runs towards sequins, latex, and lamé. And her attractiveness is unquestionable, based as it is on a combination of razor-edged cheekbones, exuberant self-confidence, and a sense of humour that can pivot from the beautifully surreal to the elegantly cutting.

But what viewers who don’t share Dharmoo’s South Asian heritage are missing is that Bijuriya’s Hindi name means “thunderbolt”. The seeming incongruity between “unsettling blast from heaven” and “intricately worked trinket” is an integral part of Dharmoo’s stagecraft, as are the various ways in which different audiences will perceive his first full-length drag show.

Onstage, the gifted singer, cellist, and composer explains in a telephone interview, Bijuriya articulates “a kind of inner dialogue between what it is to be a drag artist and what it is to be a composer trained in the western classical canon, and the questions that arise from that.

“There are tons of specific references in the piece: Bollywood titles, little bits of lyrics,” Dharmoo continues. ”But it’s all really, really popular and obvious if you know it. If the audience is mixed enough, it reveals how references hit home in a really comedic way or in a touching way with the people who know them: South Asians, or Bollywood fans, or whoever happens to know them. But for those who don’t, it becomes a really interesting position. Sometimes they’re more used to getting the codes of a theatre production, or the references, and there’s something exciting about being confronted with one’s own ignorance—and I mean ‘ignorance’ in a realistic-slash-positive sense. Like, we can’t know everything! That’s the truth, but I don’t think everyone is confronted with that reality equally.”

When Bijuriya made her full-length debut in Montreal earlier this year, one of her four performances had more queer South Asians in the audience than the others. “People were laughing way harder at some stuff, and singing along to things,” Dharmoo reports. But that didn’t alienate others in the crowd: instead, it proved intriguing. “There was something really cool for them about not getting it it,” he notes.

The move into drag has been some time in the making. When I interviewed Dharmoo for Toronto’s Musicworks magazine in 2016, he was just beginning to enjoy the uproarious success of Anthropologies imaginaires, an interdisciplinary solo show which he invented and performed diverse faux-ethnic musics, then hired onscreen actors to impersonate academic talking heads giving sometimes ludicrously off-base commentary. (Somehow this managed to be both hilarious and sobering, at least for those of us taxed with writing about other cultures’ music.)

“The next work will be about brownness,” the South Asian/Trinidadian/French Canadian artist told me at the time. “It will be about mixed race, mixed identity, mixed cultural references. How I would define it now, in a kind of vague and safe way, is that I want to play with very symbolic cult songs, or cult aspects of Indian and nonresident Indian life, like in the South Asian diaspora in the U.K. or the U.S. or Canada. Old film songs that everyone in India would know and Carnatic music and people like M.I.A. or Das Racist—like, really high-art/low-art references.”

In the Montreal drag scene, he found the perfect venue to hone Bijuriya’s look, appeal, and sly social commentary. Through a series of grassroots showcases he found a new way to express a radical vision of race, gender, and what it means to be an artist—a vision that’s laid out in surprisingly succinct form in the online trailer for Bijuriya’s Queer Arts Festival show. “To shock, ignite, empower and delight,” the drag diva sings in her upbeat, anthemic theme song. “Make art, connect, engage and reflect.”

All eight items on Bijuriya’s agenda are inseparable, but of them, “delight” might be the most important. “There’s different reasons why I do drag, and one of them was the lack of delight in what I was doing before,” Dharmoo says. “Composing, as an art form, has never brought me much delight—or anyone delight. You get some sort of validation if a piece is successful, but it never really feels like delight. It’s more like passing a test…. I just felt like I needed more of that idea of sharing joy, and having joy, and having joy not just in the result but the process, also.”

This joyous generosity carries over into other aspects of Bijuriya’s mission. The act of putting a brown, queer drag artist at centre stage offers affirmation to other racialized and gender-nonconforming people, while the sheer abandon—and, at times, strangeness—of the Bijuriya persona asks other audiences to enjoy the spectacle while questioning their prejudices.

“There’s multiple entry points,” Dharmoo confirms. “So, yeah, it’s for South Asian queers and allies, but also for anyone who’s a bit identity-confused these days—mixed-culture, first-gen or second-gen immigrants—and also for people that like art and that like music and that like to see things that aren’t conventional.”

Count us in.