Kevin Griffin • Published June 30, 2016

Drama Queer is a mass of contradictions — and that’s exactly as intended.

It has works that are both utterly beautiful and shockingly disturbing. It has provocative political works and quieter intimate works. It also has works that are designed to evoke an emotional response in the viewer.

Drama Queer is easily one of the best art exhibitions of the year in Vancouver. It’s a shame it’s only up for nine days. Drama Queer is on display until later today — Wednesday, June 29th — not Thursday, June 30 as previously indicated. The exhibition ends at 10 p.m.

There are outstanding works by local artists and a lot of work by artists from the U.S. and Europe that I’ve never heard of or seen before. Works in different mediums are treated with an egalitarianism that’s rare in Vancouver. Contemporary painting which usually has to fight for its critical existence here is given a place alongside works in other mediums such as photography, video and text-based works.

As well, the didactic panels are well written, understandable and devoid of art talk. For the most part, they convey just the right amount of information to put the works in context and help viewers understand what’s in front of them.

Drama Queer sets its tone right at the start with three photographic works by Del LaGrace Volcano. The one I found most powerful shows the face of an African-American woman in tears wearing men’s formal clothing from the 19th century. Inspired by the story of an American slave who passed not only as a man but also as white, the portrait captures what it must be like for someone to be trapped in socially-constructed blackness.

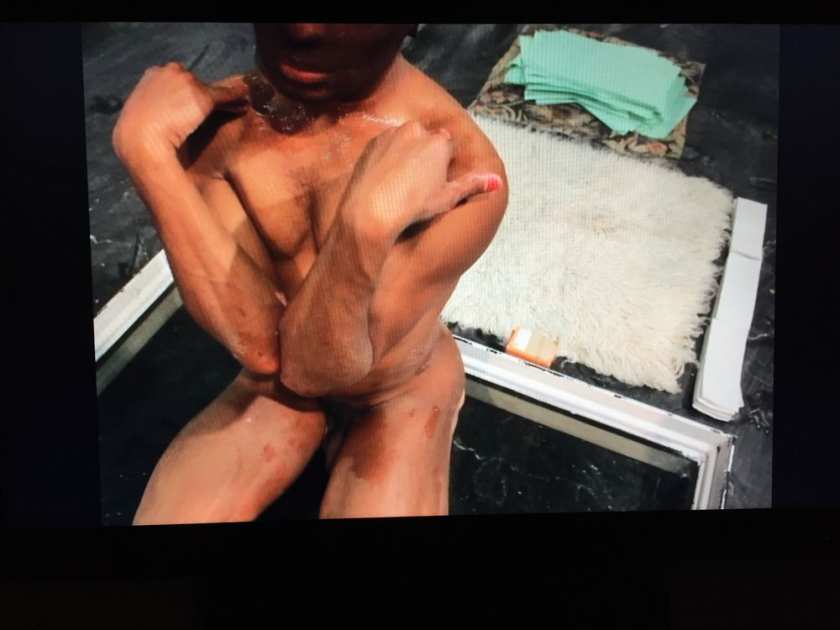

Hips by Andrew Holmquist in Drama Queer. Vancouver Sun

The exhibition includes three epic historical paintings by Attila Richard Lukacs inspired by the second U.S.-led second war against Iraq. Of the three, my favourite is 7 Devils Dead, a painting full of soldiers, devils, weapons and young men.

In the left foreground are a group of four U.S. soldiers. One without a helmet looks directly at the viewer with knowing eyes as he holds a grey gun, the vertical barrel and colour echoing oil derricks in the landscape behind. The gun is connected by a drip to a pink skeleton of death floating cavalierly on its side in the space above. His skull is a cigarette ashtray. Over its head written in text designed to look like smoke is the ironic phrase ‘Why Can’t I Quit Smoking.’

Strapped to the skeleton’s left arm is a hockey stick that morphs into another gun which shoots a bullet and rips apart the chest of a man swinging a cricket bat riddled with bullet holes that spells Git Mo. Below, a naked young man looks like he might be flying is led away by a blue devil. The naked youth’s right leg is caressed and maybe held back from death by another U.S. soldier who has an erect penis in place of his right arm. On a chain, the soldier has a tombstone that reads ‘My Beloved Boner RIP.’ It’s a great painting that not only acknowledges the homoerotic appeal of all-male environments but also the deadly consequences of being at war against other men.

I found myself lingering for several minutes on three photographs by Laura Aguilar. They’re abstracted portraits of the artist’s fleshy, Rubenesque body in a desert-like landscape.

Grounded 107 shows the artist lying on her side on a grey boulder. I had an immediate response to seeing her soft flesh on top of a hard surface: it produced a sensation that rippled down the back of my neck. I could feel the rough hardness of the stone against my skin.

Aguilar has abstracted her body so much that I couldn’t tell which end was which. Was the limb extending down into a dark cavity her leg or her arm? Aguilar’s self-portraits deny showing her face as one of the usual markers of individual identity. Their setting also made me think of the desert paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe.

Just What Is It About Today’s Homos That Makes Them So Different, So Appealing by Joey Terrill in Drama Queer at the Queer Arts Festival, 2016 [PNG Merlin Archive] Vancouver Sun

Kent Monkman has a wonderful work in the exhibition called Dance of the Berdache. It’s a five channel video projected onto synthetic buffalo hides in the main exhibition hall. The work is an exploration of identity and how the contemporary idea of ‘Indian’ is a mixture of old and new, past and present, western and indigenous. Accompanied by a soundtrack of traditional aboriginal singing along with orchestral music, it features indigenous dancers performing a mix of movement styles from Hollywood, acrobatics and indigenous traditions. In the centre, Monkman performs as Miss Chief Eagle Testikle. She’s a cross-dressing berdache who, as Monkman has said, “looks back at European settlers.”

As artist Paul Wong pointed out to me, showing Monkman’s video in The Roundhouse works far better than showing it in a traditional white cube. The Roundhouse was originally part of a complex of buildings designed to service the original steam trains which brought settlers to the western terminus of the CPR. The Roundhouse is a building whose history embodies the colonialism that inspired Monkman’s video.

There were many other works that stood out in the exhibition. One of Joey Terrill’s paintings (above and detail below) takes its title from the collage by Richard Hamilton that’s often called the first example of pop art. Terrill’s Just What Is It About Today’s Homos That Makes Them So Different, So Appealing depicts examples from his daily life as a Mexican-American living in Los Angeles. Sharing the canvas with a playful presentation of sex, AIDS pills and various consumer items such as a bottle of Coca-Cola are several monarch butterflies which symbolize the Chicano community. In a few expressive but controlled gestures of paint in lime green, Andrew Holmquist combines both masculine and feminine in Hips (above). Photographs of Cassils record a performance by the transgender artist when she attacked a 300-pound pile of clay. Her insanely muscular and ripped body is the result of working out for two years. Keijaun Thomas’s slow, methodical almost ritualistic movements in his video installation The Poetics of Trespassing (detail above) were hypnotic and powerful. The video depicts the harshness of racism by softness when the brown skin on the artist’s back and shoulders is covered with a dusting of white flour.

The exhibition also included works that I found difficult to look at.

One in particular is from series of erotic photographs by George Steeves, a Nova Scotia artist who identifies as straight. One of them shows an older man seated awkwardly at the bottom of a banister. He’s naked and has a big erection that parallels the verticality of the posts on the stairway.

The photograph provoked a response because it made me confront my own fears of aging and sex. It was his expression that I found particularly disturbing: he appeared totally possessed by his fetish. With his missing and blackened teeth, he no longer looked human. He looked like a ghoul.

The one work that I found by far the most troubling was Naked Boy Cutting by Andreas Fuchs. It shows a naked young man with several piercings and tattoos in the moments after he’s cut his left arm. He’s bleeding profusely. As a photograph it reads as a document of an event in a pristine white environment.

The didactic panel says that the photo embodies the contradictory drives of masochism and sadism in one person. The young boy is both the active partner inflicting pain and the passive partner receiving it. Although it’s difficult to get inside the mind of someone, the description seems a fair one. He looks as if he’s amazed at what he’s done to his body.

This is one case where more information would have been helpful. It wouldn’t have reduced my visceral reaction to the photograph, but it would have helped to know how this one image fit into the artist’s other work and whether the one in the exhibition was part of a series. On its own, it looks provocative for its own sake.

As well, I kept thinking about the relationship between the model and photographer. Was there a sense that the model was performing for the camera and making the wound deeper and more dramatic for a ‘good’ picture? Did the photographer ask for a deeper cut to produce more blood? The photograph was so foreign to my own experience that it both fascinated me and repelled me.

Drama Queer is curated by Jonathan D. Katz, one of the leading queer art historians and curators in the U.S. He’s an associate professor and director of the doctorate program in art history/visual studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo. I’ve written previously on both Drama Queer and Katz.

Drama Queer is part of the Queer Arts Festival. The art exhibition ends today while the festival continues to June 30th.

Detail from Just What is It About Todays Homos That Makes Them So Different, So Appealing by Joey Terrill in Drama Queer. Vancouver Sun

*Grammatical corrections made Thursday, June 30, 2016. See original article here.